Mass Data Collection

Roughly 160 countries issue biometric passports today. Face recognition is most commonly used to verify that the traveller who presents their passport is who they say they are on entry and exit.

From a technical perspective, the choice to use AI is not fundamentally a problem due to the high volume of travellers that an airport receives. Various studies debate that AI has outranked humans perception with face verification. Of greater concern is:

-

how governments may store and use biometric data as a means for violating privacy or profiling marginalized people.

-

how and what the model for face detection is trained on to produce reliable results for verifying the faces of underrepresented minorities, such as Black, South Asian, and Arab people.

-

performing the above fairly requires an ethical collection of images from visible and ethnic minorities’ faces–however, companies can just as likely circumvent this need by collecting user-submitted selfies from the internet for training datasets without the individual’s consent

Black activists and scholars have warned of the potential harm the use of facial recognition may cause Black and darker skinned people due to their history of disproportionate encounters with law enforcement through stop-and-frisk, carding, misidentification and incidents of brutality.

A 2021 study, “Comparing Human and Machine Bias in Face Recognition” found that both humans and AI are inaccurate at recognizing darker-skinned women, in particular, IBM’s model.

Carnegie Mellon Endowment for Peace, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Algorithm Watch “The Face Recognition World Map”, 2020.

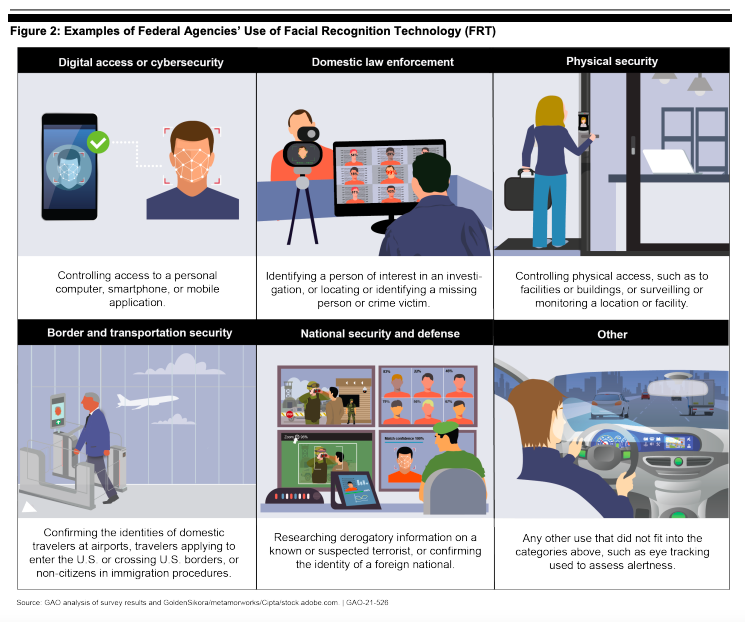

Figures from the GAO report on how face recognition is used by Federal Agencies.

Source: United States Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Requesters. Facial Recognition Technology: Current and Planned Uses. August 2021

AI-Driven Racial Profiling

The German National Socialist government is an infamous historical example, however similar acts of racial profiling that lead to persecution continue today.

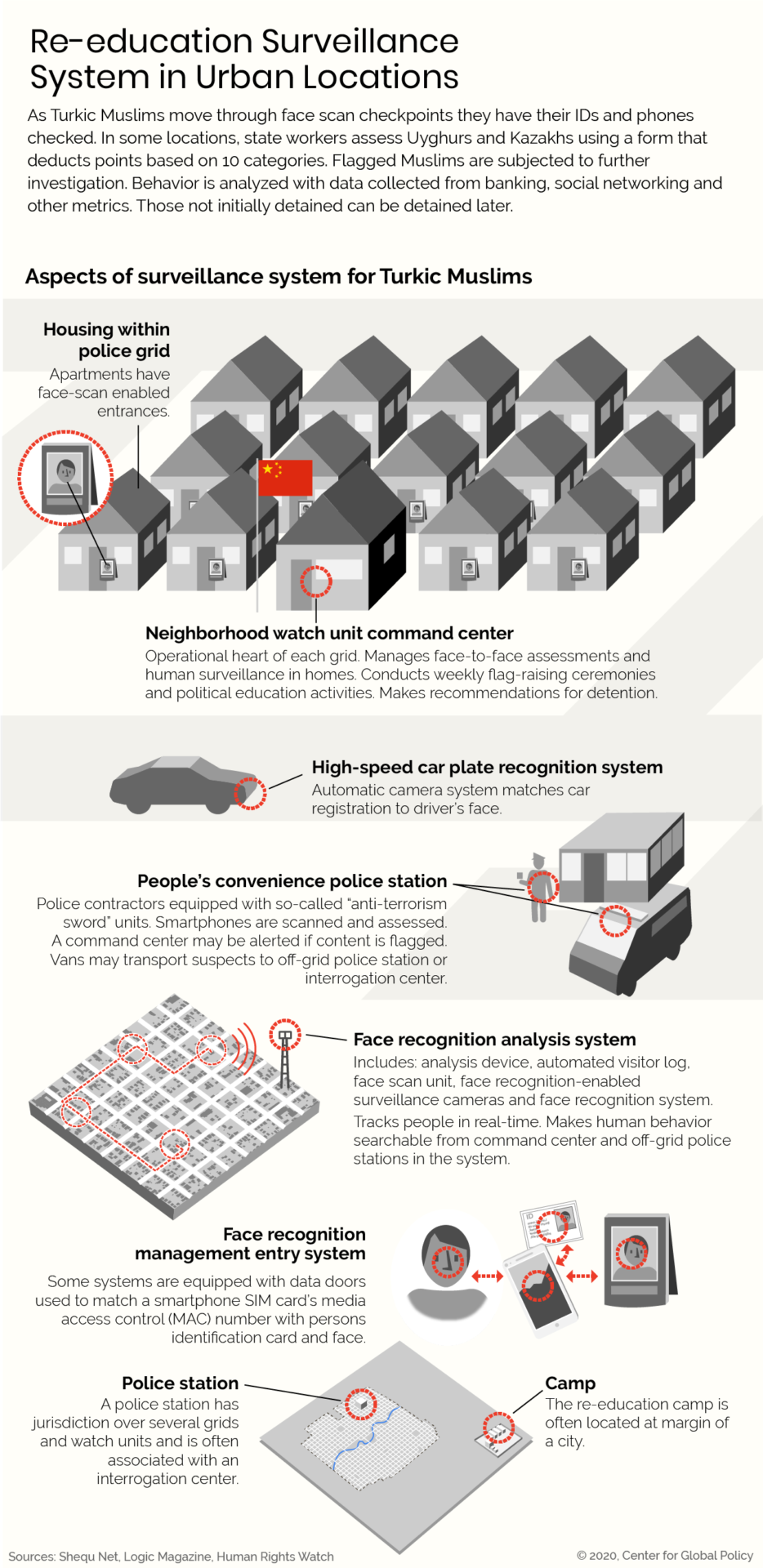

After the Chinese government rolled out the “Peoples War of Terrorism” law in 2014, the Uyghur Muslim population in Xinjiang has experienced increasing surveillance and persecution through check points, deportations, sudden disappearances, sterilization, forced labor and detention.

Since 2017, over 1 million Uyghur Muslims have been reportedly detained at internment camps, 职业技能教育培训中心, or “vocational skills education and training centers” in Xinjiang. Under a guise of a “Physicals for all” campaign, the Chinese government collected 19 of 22 million of Xinjiang’s population’s DNA.

The recent publication of “The Xinjiang Police Files” on May 24 2022 of XAR police documents depicted some 5000 faces and conditions of Uighur detainees from 2018. Based on the files and previously leaked cables, Adrian Zenz estimates 12% of the local Uighur populace in Xinjiang is currently detained.

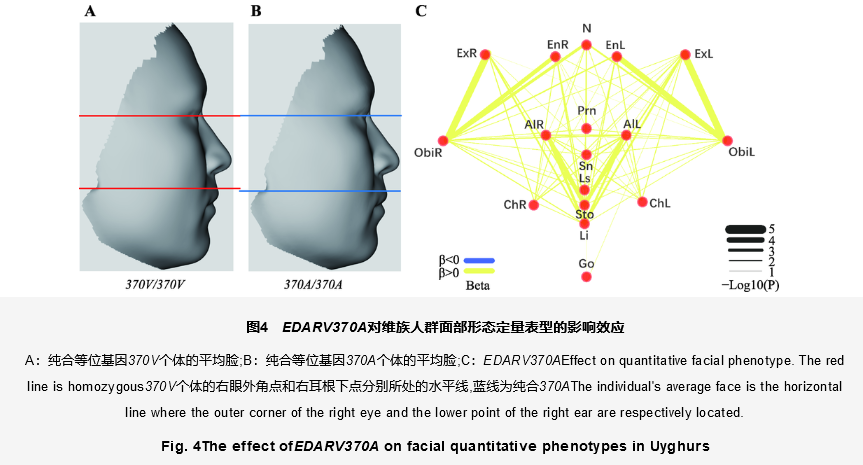

Diagram from 1 of 4 papers from Leon Schneider’s analysis of recanted papers published by Chinese geneticists due to non-consensual use of state collected biometrics.

Security camera supplier Hikvision showed off a feature for detecting Uyghur “minorities” at the 2018 AI Cloud World Summit.

All promotion material advertising these features were redacted or removed by Hikvision after IPVM and western media highlighted its presence.

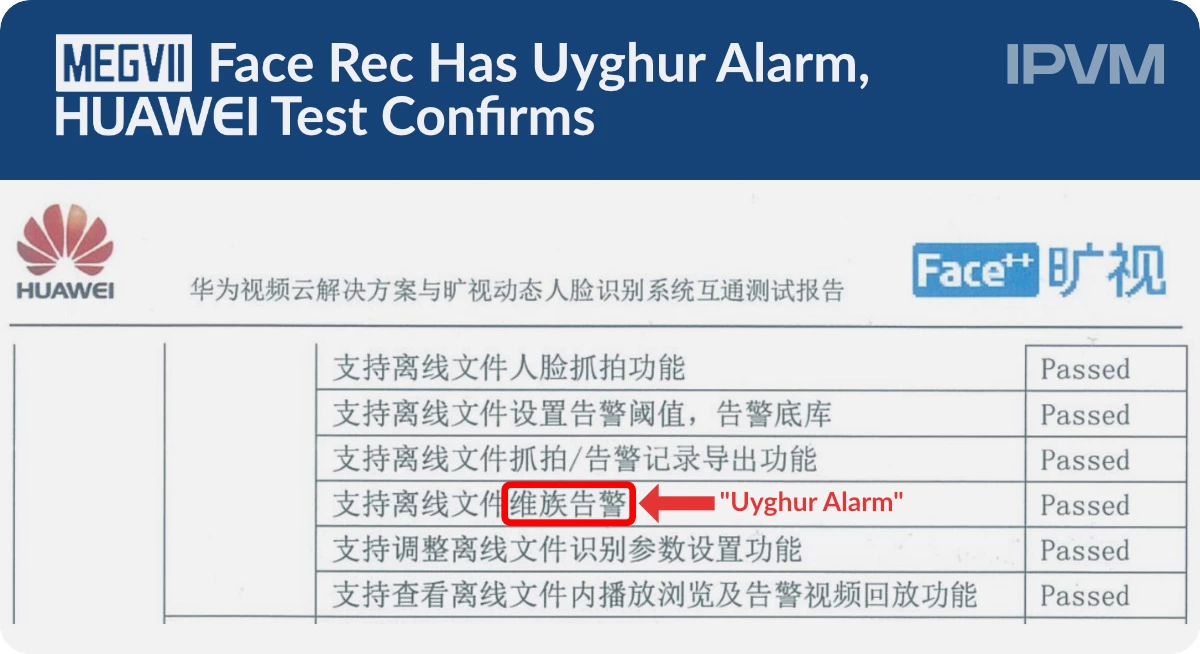

Back in 2019, IPVM revealed that Huawei and Megvii applied for a patent on Uyghur face detection. The application declared:

“It is necessary to divide the ethnicity classification standards, for example, [the portraits] can be divided according to Han, non-Han and unknown. Similarly, it can also be based on actual needs [...] for example, it can be divided according to Han, non-Han and unknown, or according to Han, Uyghur, non-Han, non-Uyghur, and unknown [emphasis added]”

Megavii and Dahua were also called out for developing and testing a “Uyghur Alarm” for reporting Uyghurs to Chinese authorities.

Note: IPVM’s coverage was published as a report that was presented to an independent people’s tribunal in the UK, but at this time of writing, international court justice has not been pursued yet.

In a similar Orwellian fashion, Israeli authorities have been using different surveillance mechanisms to identify and track Palestinians in the West Bank area.

Map of Israeli and Palestinian territories in 2019.

2019 was a busy year for Anyvision (now renamed Oosto), an Israeli-based AI startup. At the time, the company had already set up face recognition devices at 27 border-crossing checkpoints used by Palestinians.

An Anyvision pilot that ran at a Texan highschool found that students were tracked as much as 1100 times through a week, which led to tech observers to warn of potential for misuse.

Much like the logic of a “No Fly List”, Anyvision advertised a feature that allowed for creating watchlists from databases of faces for realtime detection of “Persons of interests” (POI). (To their credit they also have a whitelisting feature.) The feature was called “Better Tomorrow” but has been rebranded “OnWatch” since they rebranded as Oosto.

In 2021, the Israeli Defence Force rolled out a “Blue Wolf” smartphone application, which uses surveillance camera and still images to compare against a government database of Palestinian faces. Blue Wolf assists with identifying and determining whether the Palestinian subject should be arrested, detained or allowed to continue with their day.

Reports of prizes for the most photos captured and shift quotas have emerged as a result of government orders to populate the database. Within Hebron, CCTV cameras are able to scan Palestinian faces prior to showing their ID at checkpoints.

A companion application, White Wolf, allows Israeli settlers who employ Palestinians to perform identity verification.

Footnotes

Elizabeth Dwoskin. "Israel escalates surveillance of Palestinians with facial recognition program in West Bank”, Washington Post, Nov 8 2021.

Connor Healy, “Uyghur Surveillance & Ethnicity Detection Analytics in China”, IPVM. August 20, 2021

National Institute of Standards and Technology. “NIST Study Evaluates Effects of Race, Age, Sex on Face Recognition Software”,** December 2019

Adrian Zenz, “The Xinjiang Police Files: Re-Education Camp Security and Political Paranoia in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region”. The Journal of the European Association for Chinese Studies, 3, 1–56. 2022

Omar Shakir. “Mass Surveillance Fuels Oppression of Uyghurs and Palestinians”,** Human Rights Watch. Nov 24, 2021